Foundations are a driver of social change. They make social mobility possible and contribute significantly to a successful society. The available means for foundations to achieve these objectives are, among others:

- granting of prize money, scholarships, and publication grants,

- organization and promotion of conferences and workshops,

- establishment of educational and integration programs,

- project funding, or

- establishment of endowed professorships – to name but a few.

This explains why 549 foundations were newly established in Germany in just one year (2017).

At present, however, the roughly 22,000 foundations in Germany use just a very small portion of the funds available to them for supporting social purposes − namely the annual revenues from asset management. With an estimated € 100 billion in investments, € 3 billion revenues distributed to social projects represent less than 3 % of total assets.

Hence, the board of directors of the F.B. Heron Foundation has aptly stated, “A foundation should be more than essentially a private investment company that uses its excess cash flow for charitable purposes”.

Foundations could increase their impact enormously if effective actions were taken not only as to the use of funds, but also in regards to the funding sources. While the focus of the discourse about impact has so far been primarily on the use of funds by foundations, the impact of the source of funds, i.e., the foundation’s assets is increasingly becoming the focus of attention.

How could an impact statement of foundations be drawn up that takes into account both of generating funding and of how they are used, and is therefore relevant for managers and founders of foundations? According to the discussion of the impact logic with social projects, one would then have to think about a theory of change of foundations. However, what makes a foundation effective? In view of the great heterogeneity in the foundation sector, can “impact” even be defined uniformly at all?

Each foundation is different from the others in terms of its objectives, capital investment, and size. However, there is one thing that they all have in common: the intention to contribute positively to the common good. This aspiration ought to be the driver and lowest common denominator of all the parties involved. Hence, a simple impact equation could contain various areas of activity of a foundation in which – in addition to the classical project work – impact can be achieved. Then, in a next step, these categories could be examined in respect to their characteristics. The various areas of activity can also be referred to as “impact axes”, and the characteristics as “degrees of impact”.

In the run-up to the German Foundations’ Conference 2018 in Nuremberg, the authors took a closer look at these dimensions of impact. The objective here is not to align all foundations uniformly, but to encourage each foundation to structure and align its impact over all areas in accordance with its purpose.

Impact Axis Capital Investment

Foundations command assets from the past that they have to preserve for the future, and should use as well as possible in the present. We distinguish between legacy capital, and non-legacy capital. Legacy capital is the capital that gives a foundation its identity, and is sold only in exceptional situations. That can be forests or land ownership, local real estate portfolios, or large participations in companies, which might even bear the same name. In our opinion, legacy capital even forms by far the greater part of German foundation assets. Non-legacy capital is capital that can be relatively freely disposed of. These are mainly capital market investments, real estate funds, and investments in private equity funds.

Impact Axis Framework Conditions

An analysis of the social aspect will continue to be dominated nationally for the foreseeable future. While companies have long been familiar with the European single market, cross-border activity is still an exception for philanthropists. Many foreign social enterprises and non-profit organizations look enviously towards Germany because it has a lively and financially sound foundation and funding landscape. This is especially true in comparison with Eastern European countries, in which private commitment is still very low. Foundations can exert an influence on their framework conditions. Changes can be made indirectly via association structures, or directly through the establishment and support of intermediaries.

Impact Axis Commitment

This impact category raises the question of how the impact of project funds can be increased by additional commitment. In principle, foundations have three ways by which they can increase their impact through commitment. They can either allow access to their infrastructure, help acquire resources of third parties, or enable and scale projects through their reputation and networks.

Impact Axis Operational Design

Apart from their funding activities, foundations are also entirely normal organizations that buy products and services, go on business trips, and send gift cards at Christmas. An impact-oriented strategy of foundations also ought to keep an eye on these resources and their optimal use. This impact axis, which one could also call “operational design”, includes possibilities to achieve an impact that is not directly connected with a foundation’s funding activities, but with its entrepreneurial decisions.

Degrees of Impact

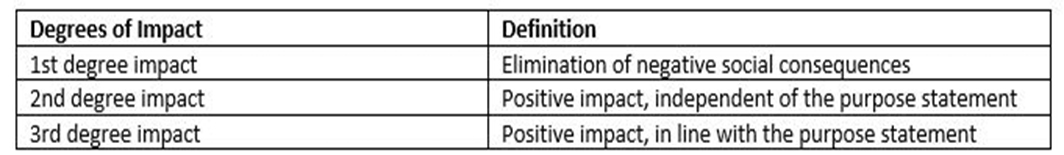

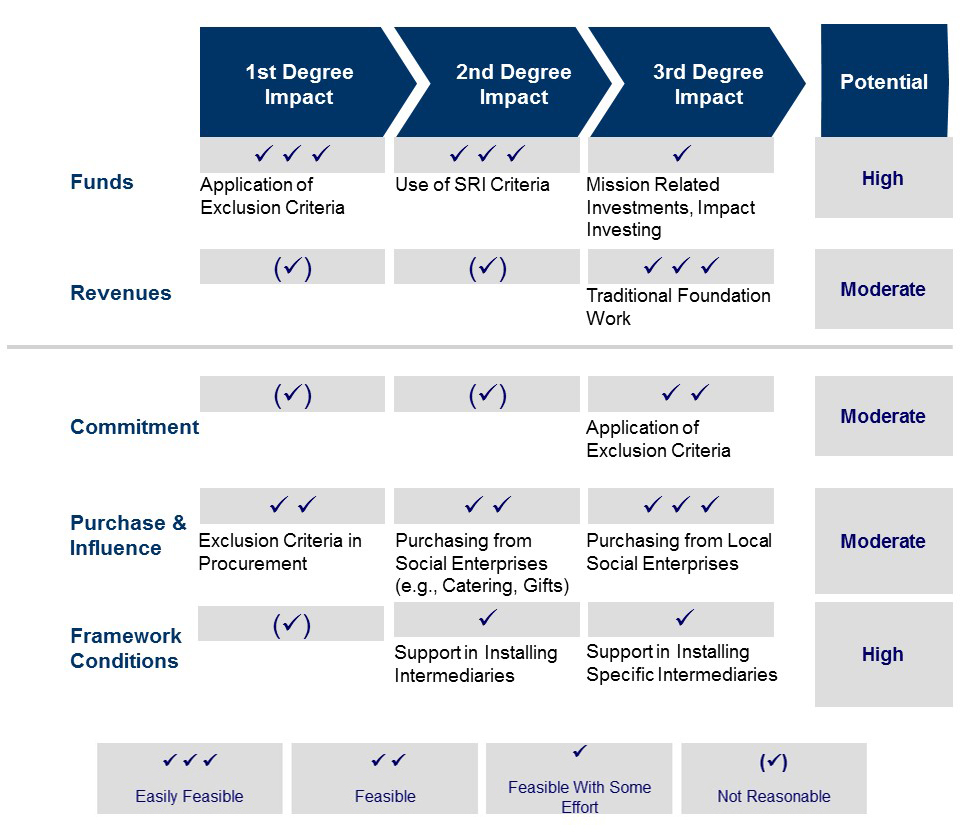

In a next step, these impact axes can be subdivided in accordance with their characteristics. The model we have proposed has three degrees of impact, which are defined in terms of the type of impact. Impacts of the first degree are impacts that eliminate negative social consequences. Impacts of the second degree are about achieving a general positive impact. Impacts of the third degree have a positive effect that is even in keeping with the foundation’s purpose.

The following diagram shows all impact axes with examples and an assessment of their potential:

Consequently, the overall impact of a foundation is the sum of the individual impacts in the various categories.

Such an impact statement also ought to be compatible with other common reporting standards (e.g., GRI Global Compact or Social Reporting Standard). This would presuppose that the same terminology is used, and that the systems of indicators are in agreement. However, at the same time, the complexity would have to be reduced as far as possible so that a low-threshold, easy to implement instrument can also be created for small and medium-sized foundations.

Further Reading:

- Achleitner, Ann-Kristin, Andreas Heinecke, Abigail Noble, Mirjam Schöning, and Wolfgang Spiess-Knafl. “Unlocking the Mystery: An Introduction to Social Investment.” Innovations 6 (3): 145–154.

- Glänzel, Gunnar, and Thomas Scheuerle. 2015. “Social Impact Investing in Germany: Current Impediments from Investors’ and Social Entrepreneurs’ Perspectives.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 1–31.

- Höchstädter, Anna Katharina, and Barbara Scheck. 2015. “What’s in a Name: An Analysis of Impact Investing Understandings by Academics and Practitioners.” Journal of Business Ethics 132 (2): 449–475.

- Letts, Christine W., William Ryan, and Allen Grossman. 1997. “Virtuous Capital: What Foundations Can Learn from Venture Capitalists.” Harvard Business Review 75: 36–50.

- Milligan, Katherine, and Mirjam Schöning. 2011. “Taking a Realistic Approach to Impact Investing: Observations from the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Social Innovation.” Innovations 6 (3): 155–166.

- Spiess-Knafl, Wolfgang, and Barbara Scheck. 2017. Impact Investing. Palgrave Studies in Impact Finance. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Spiess-Knafl, Wolfgang, and Stephan A. Jansen. 2013. Imperfections in the Social Investment Market and Options on How to Address Them. Ex-Ante Evaluation for the European Commission. Zeppelin University, Germany.