Globalism, mobility, intercultural competence and internationality – all this would not be possible without the command of multiple languages. To put it precisely: It would not be possible without English. At least not in most cases, because English is by far the most dominating language of the world. But how did this dominance develop? And what about the much praised multilingualism?

The EU promotes the multilingualism of its citizens

24 officially recognized languages are spoken within the EU[1]; in addition, there are more than 60 regional and minority languages, plus many indigenous languages of migrant communities.[2] It is the declared goal of the EU to support the multilingual competence of its citizens, as it spells decisive economic, social and professional advantages. Preservation of a language – thus the official approach of the EU – also leads to the preservation of cultural traditions, regionalism, and cultural uniqueness. The right to one’s own language is considered a basic human right; whereas contempt of bilingualism, the negligent treatment of children with other native languages at school is condemned as linguicism, as discrimination based on lingual diversity.[3]

Bilingualism or multilingualism facilitates learning additional languages, broadens the horizon and sharpens awareness of diversity, but also for a person’s own faculty of speech; it opens professional perspectives, not to mention the advantages of being able to directly communicate with people speaking other languages. However, these (and probably many more) advantages, are opposed by one significant drawback: Learning a language requires great efforts in terms of committing time, energy and money.

Asked for the circumstances that would facilitate or promote learning of a foreign language, 29 percent of the EU citizens interviewed in a Eurobarometer survy answered, that language courses should be free. 19 percent would learn a language only if they were paid for it. Asked for possible obstacles that would most probably prevent them from learning a foreign language, a total of 34 percent of the interviewed stated that they lacked the required motivation. Lack of time (28%), excessive costs (25%) and lack of language talent (19%) were stated as additional reasons.[4]

A common language for Europe?

Altogether 53 percent of the EU citizens that were interviewed believe that the European institutions should use a common language to address their citizens. But which language? This question was not asked, but we have good cause to believe that the majority of them would have chosen English.[5]

The economic strength of the big English-speaking industrial nations also defines the economic significance of English. The changes of the global economy can also have an impact on its importance. The Gross Language Product (GLP) calculates the proportion of the languages spoken in the relevant country with the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the same, i.e. the economic significance of a language.[6] Even when based on differing calculation methods, the importance of English in respect of the GLP stands out far in comparison with other languages: Japanese, German, Spanish, French, Russian and Chinese.

67 percent of all the EU citizens stated that English was the most useful language for them.[7] In addition to all sorts of benefits – English is the language of the Internet, of modern music, international communication etc. – the perceived advantage also refers to career and earning opportunities, which, in an internationally interconnected economy, are available only by mastering a foreign language, and in this respect – above all – English. Thus, English is literally worth a mint.

Countless world’s Englishes change the English language

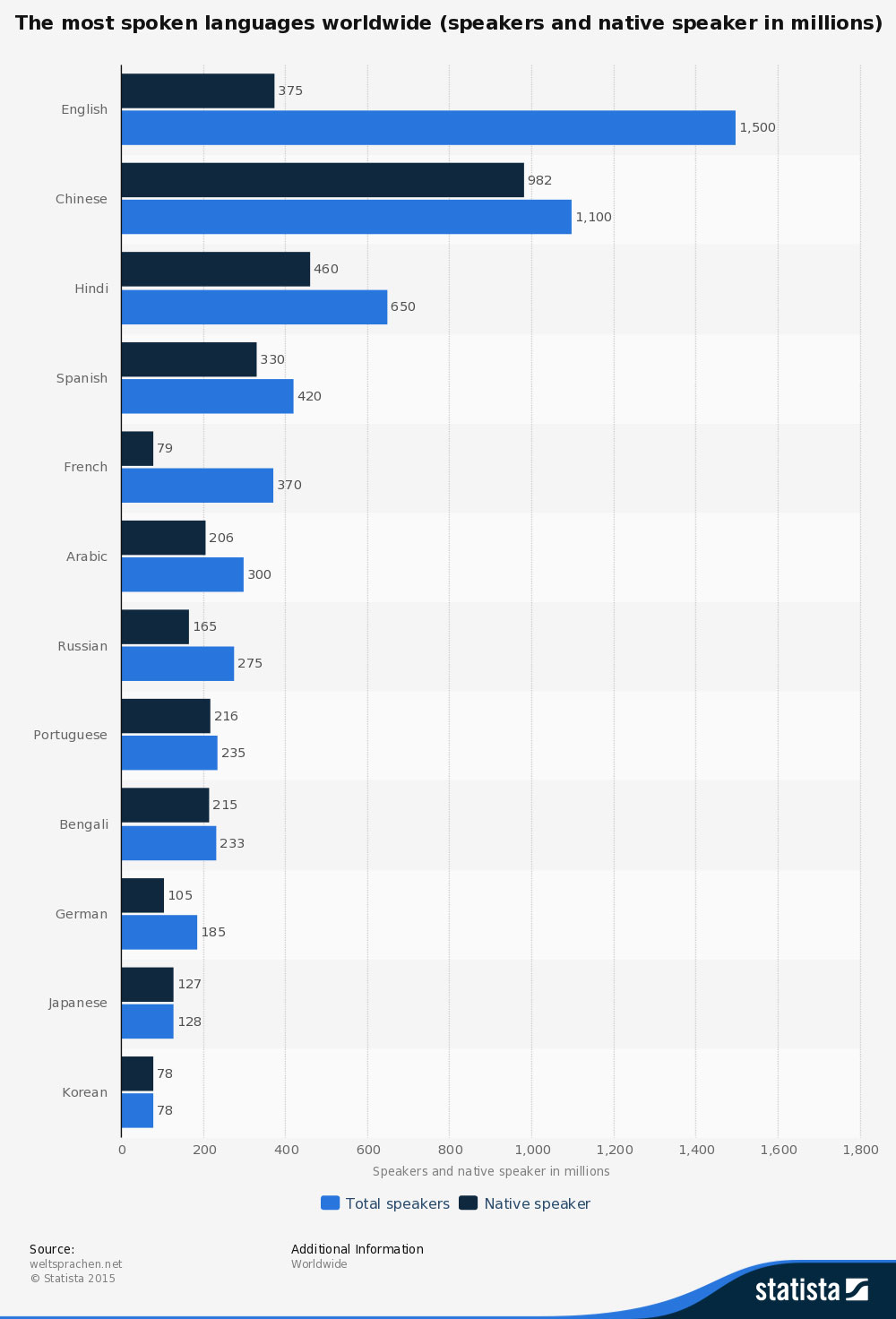

Today, the meaning of the English language in international communication is undisputed, and some may even ask themselves when English will becomethe world language – replacing other languages altogether. Linguists, however, have started speaking of the “World’s Englishes”, of the countless varieties of English, quite a while ago. The number of people speaking English as a foreign language (approx. 1,500 million people) by far exceeds the number of native speakers (approx. 375 millions)[8] and these “L2 speakers” have changed and are changing the English language with their very own culture, pronunciation and syntax.

There are already significant differences even between British and American English. But the other variants of English have also developed more and more independently, according to the opinion of some researchers, so that in the future, various English-based languages will emerge.

Turning into a Lingua Franca, is English threatened to suffer the same fate as Latin? The development of languages follows the development of societies[9], and in the long run, we must accept mankind’s multilingualism. But this also means an all-clear in a twofold sense: Mankind’s multilingualism will remain, but simultaneously, the supremacy of English will persist for quite a few eras to come.

[1] European Union (2012): Multilingualism,http://europa.eu/pol/mult/index_en.htm (as of 1.12.2015).

[2] Special Eurobarometer 386 (2012): Europeans and their Languages, European Commission,http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_386_de.pdf (as of 1.12.2015), p. 2.

[3] Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove (Ed.) (2012): Language Policy and Linguistic Human Rights, in: Ricento, Thomas (2006): An Introduction to Language Policy. Theory and Method, Blackwell, p. 273-291.

[4] Special Eurobarometer 386 (2012), p. 110.

[5] Special Eurobarometer 386 (2012), p. 131.

[6] Graddol, David (2000): The Future of English, p. 28.

[7] Special Eurobarometer 386 (2012), p. 78.

[8] Statista (2015): Meistgesprochene Sprachen weltweit (Weltsprachen.net) (The most frequently spoken languages worldwide)

[9] refer to e.g. Dixon, R.M.W. (1997): The Rise and Fall of Languages, Cambridge, in particular p. 58 et seq.