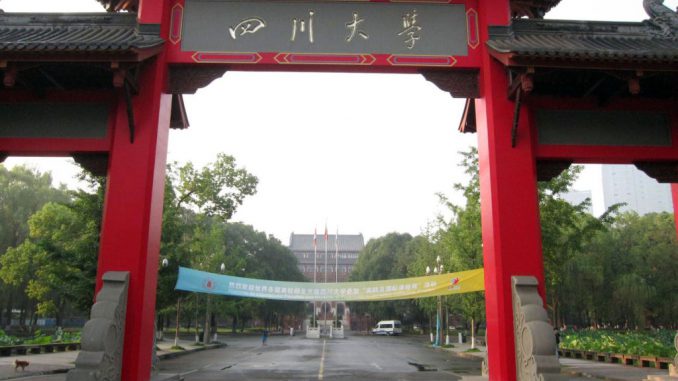

As in previous years, Sichuan University in Chengdu hosted a two-week “University Immersion Program” for its students: At one of the China’s most distinct universities, about 150 professors from all over the world lectured and taught for thousands of Chinese and also some international students.

The array of subjects taught was very much diversified, and MBS was represented at Sichuan University with an extract of its course on the “Success Factor Happiness”. More than 100 students had booked the course to learn more about the countless aspects of happiness and its integration into economic approaches.

In one of the course’s first exercises, students had to rate their perceived current life satisfaction with a number between 0 and 10 (the so-called Cantril ladder). With a result of 6.21 points, the course’s group of Chinese students showed a slightly lower result than the comparable group of German students. Female students seemed to be somewhat happier than their male co-students. Male students, however, achieved a slightly higher value (6.53) than their female counterparts (6.45) in answering the question if they saw a meaning in what they were doing with their lives.

But what is it that makes students happy in China? The course attendees from Chengdu as well as those from Munich stated that “happiness” was generated by doing something with friends or passing an exam. There are, however, some distinct Chinese characteristics: “Good food” and contact with the family (even if only by phone) were very often mentioned as happiness factors. Travelling in general and visits to the family, which often lives thousands of miles away, were frequently stated. Some students even named “being alone” as a happiness factor, possibly owed to the fact that, as a rule, Chinese students share their room with three other students and always and everywhere encounter co-students on the campus. Material wealth, however, was amazingly seldom quoted by Chinese students.

These results, of course, are based on a small and also choice group of students of business administration in their first semesters. They are definitely neither representative for all students or even for all of China. Nevertheless, these figures as well as the answers to the open questions allow first interesting insights particularly into the culturally-conditioned and life situation-related differences of the happiness factors of Chinese and German students. These findings are certainly not unimportant for universities and business schools, enabling them to generate a learning environment that can boost successful studies.