You want to know if your partner has embezzled funds or is planning to leave the company. You want to know the true future plans of the politician you are just interviewing. You want to know where your partner spent the last night. You want to know what your employee really thinks about you. You want to know if your child has ever taken drugs, and if so, what drugs and how often. In short: You want the truth.

In the past few years, I have devoted myself to finding techniques for finding the whole truth, and here I present you a summary of my findings.

Situations such as those described above happen in all walks of life: There is the broker concealing the decisive defects of an apartment, the want-to-be tenant ranting of his meteoric career and secure income. There is the job candidate who declines to reveal the real reason of his job change in an interview (and also from the other perspective: The candidate who wants to know whether the promised opportunities for advancement of the new job are not grossly exaggerated). There is the almost eighteen-year-old who, at the dining table, hides the real reasons for wanting to have the car over the weekend. And there is you who just simply wants to know what your counterpart really thinks about you.

You do not want your employees to leave your office, giggling and thinking to themselves: “That idiot actually believed it!” Plus the further up you go, the more you will be lied to. A director once told me that this was the very reason he had hired business consultants: To have someone to tell him the truth about his company. A good boss, however, will know by himself when someone tries to fool him.

I will explain to you how to take a few minutes to get to the truth; how to make the right decision at crossroad moments and bring your counterpart to tell you everything he or she knows about a particular subject. If you steal a pack of chewing gum at the supermarket, what you will probably feel is not so much guilt but fear. But this changes when you lie to your wife or girlfriend or even both! The closer we are to a person, the greater the perceived guilt is!

But how do we recognize guilt? Interestingly enough, the facial expressions for grief and guilt are nearly identical: The eyes go blank, looking into space, the corners of the mouth drop1. If your partner, looking all sad, reports about being out last night with some buddies, it might well be that he/ she is not actually grieved…

From Bill Clinton to Uwe Barschel

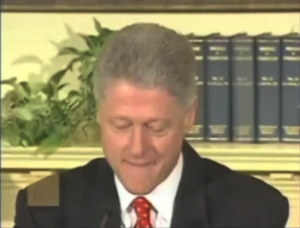

If you look at the famous vid from the late nineties in which the former US president Bill Clinton declares that he “did not have sexual relations” with Monica Lewinsky, you will notice the sad face that he puts on repeatedly, and above all when, after having made the statement, he turns to the side, heading for the exit. At this point, Mr. Clinton acts like a school boy being caught with his hand in the cookie jar, as the US psychologist Paul Ekman once put it2.

If you look at the famous vid from the late nineties in which the former US president Bill Clinton declares that he “did not have sexual relations” with Monica Lewinsky, you will notice the sad face that he puts on repeatedly, and above all when, after having made the statement, he turns to the side, heading for the exit. At this point, Mr. Clinton acts like a school boy being caught with his hand in the cookie jar, as the US psychologist Paul Ekman once put it2.

You can make out this specific expression of guilt even more clearly in Uwe Barschel. In the 1987 election campaign in the German federal state of Schleswig-Holstein, he had bugged his own office and later “discovered” the bugs with much ruckus, accusing his rival Björn Engholm of having placed them. Finally, he gave a press conference where he declared his innocence, shortly before he was found dead in his bathtub under unexplained circumstances. The film was briefly shown to me during a TV show to explain the lie indicators. I had not seen the clip before and watched closely: When Mr. Barschel had finished his statement, his shoulders slumped, he put his hands over his face and looked like the personified image of grief and guilt.

You can make out this specific expression of guilt even more clearly in Uwe Barschel. In the 1987 election campaign in the German federal state of Schleswig-Holstein, he had bugged his own office and later “discovered” the bugs with much ruckus, accusing his rival Björn Engholm of having placed them. Finally, he gave a press conference where he declared his innocence, shortly before he was found dead in his bathtub under unexplained circumstances. The film was briefly shown to me during a TV show to explain the lie indicators. I had not seen the clip before and watched closely: When Mr. Barschel had finished his statement, his shoulders slumped, he put his hands over his face and looked like the personified image of grief and guilt.

I have posted both clips for you on my Internet page.

As explained before: The closer you feel to a person, the more guilt you will feel. This is a fact that you can use. Point out your good relationships to the suspect; this will significantly increase any feelings of guilt. You can use phrases like: “Great to see you, old pal!”, or “I trust you one hundred percent!”

When I was a student, my first girlfriend once said to me: “I know for sure that you would never lie to me!” Had I lied to her, I would have felt tremendously guilty….Today, she is a judge.

There is, however, one exception: There are people without conscience – as for example psychopaths – who hardly feel any guilt and therefore cannot be exposed by this method. Fortunately, only approx. one percent of the population has this personality disorder. On the management level, however, you are four times more likely to meet them3. Consequently, if I give a presentation before 1000 top level managers, as a rule, there are nearly 40 psychopaths in the audience, preferably in the front rows. For those gentlemen, other lie detection methods need to be applied.

After testing and applying countless techniques for debunking lies, I can tell you with certainty that in most cases, nothing is easier to recognize than guilt. This “stamp of guilt” – weighing like a ton on the shoulders of the culprit – often becomes apparent in the first few seconds. In some cases at the very moment the culprit enters the door! Especially when she is a woman – because women are more susceptible to guilt than men4!

1see Nasher, Jack, 2010, “Durchschaut!”, p. 78

2see O’Connor, John: “Paul Ekman – ‘I can tell when you’re lying'”, Financial Times, November 29, 2008

3see Hare, R. D., 1994, “Predators: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths among Us”, Psychology Today, 27, No. 1, p. 54-61

4see De Paulo et al., 1993; DePaulo et al., 1996; Vrij, 2008, p. 43 f.; cf. “Durchschaut!”, p. 76