The term “Five-Year Plan” is one of the best known buzz words referring to China’s economy. Its 13th and most recent version was adopted just a few weeks ago by the National People’s Congress. First discussed in October 2015 at the 5th plenary session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, it now defines the frame structure and sets priorities for the general strategic direction of the development of the People’s Republic of China until the year 2020.

Plans Become Programs

But the plan no longer is a plan. At the 11th Five-Year “Plan” in 2006, the Chinese term “Five-Year Plan” (五年计划) had already been renamed into “五年规划“, which roughly means program or guideline. Erroneously however, even English-speaking Chinese media, and in particular those outside of China, in English and also in German continue to speak of a “Five-Year Plan”. But why is this wrong – and why is a distinction so important?

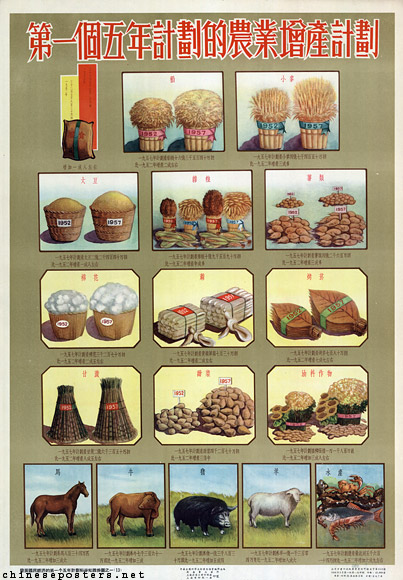

Changing the term for the strategic orientation at the 11th Five-Year Program, in particular for China’s economy, was aimed at abolishing the supposedly obsolete association with achieving plan numbers in industrial production, agriculture and other sectors.

To put it simply: Today, it is not about producing a certain number of shoes, as it was the case at the time of the first Five-Year Plans. It is about achieving improving wealth and a better quality of life for the entirety of the Chinese people within the frame of the “socialist market economy of the Chinese type”.

Thus, after the privatization waves of the eighties and nineties, a “program” had to be outlined: a program that did justice to the new economic system where planning could function only to a very limited level.

New Programs versus “Old Mentality”

Consequently, the Five-Year Program should rather be understood as strategic blueprint for the direction of the People’s Republic for each following five years. However, the pertaining change of the mind takes time. At too many occasions and in too many local governments, the “old way of thinking” prevails.

There are also reports about environment protection and the development of the local GDP, for example, that are neither realistic nor truthful. (For example, there is the recurring phenomenon that the data reported on the local level in a certain area fail to comply with those that are published by the province). Therefore, it is all the more important to encourage turning away from the obsolete planning mentality, including the change of terms regarding the original Five-Year Plans.

As far as content is concerned, the 12th Five-Year Plan (in the period between 2011 and 2015) expresses turning away from quantity planning and the adoption of a more quality-oriented program very clearly. At his point, quality-related growth was placed in the focus of China’s economic development for the first time: Excessive growth rates of past plans had led to a situation where the country engaged in ruthless exploitation of its environment which affected life’s quality in an alarming way. Accordingly, environmental goals were declared binding, and merely economic goals were subordinated.

Focus on Society’s Goals

The 13th Five-Year Plan which was now ratified (for the period from 2016 until 2020) places the focus on quality-relevant growth. The central topics are society-oriented: wealth for the population, a more even distribution of the fruits of economic growth as well as the population’s general happiness and life quality.

As a result, the objective is to double the average per-capita income of 2010 by 2020. 90 percent of the population is to be integrated into the social security systems until 2020 (i.e. 84,000,000 people more than today). Another goal is that, on 80 percent of the days, big city dwellers will see the sky again (if the weather and not if the degree of air pollution allows it). In the rural areas, approximately 56,000,000 people are to be brought out of poverty. And if they wish and can afford it, people are now allowed to have two children.

Of course, the current Five-Year Plan also includes classic elements such as the focus on a national economic development that is driven by national consumption, innovation, entrepreneurship and an upgrade of the seal “Made in China” to “Made in China 2015”. It will, for that reason, become all the more important in the coming years that Chinese companies in the provinces learn to understand and implement the concept of strategy in its width, and thus are in a position of leaving behind the mentality of planning figures – as the Government has already been doing since 2006 by introducing a new term for Five-Year Plans.

You can look into all Five-Year Plans and Programs in Chinese on the website of The Communist Party of China under http://dangshi.people.com.cn/GB/151935/204121/

The figure is part of the IISH/ Stefan R. Landsberger Collections and courtesy of chineseposters.net.