The yearning for a world where people treat each other and their environment with more care and respect is probably the common wish shared by the vast majority. So far, governmental systems are the most important players in designing this world and achieving this goal: Through legal systems and financial redistribution, they ensure that societies manage to find peaceful solutions for their economic and power-political conflicts, and that environmental conditions worth living in can emerge.

In addition to governments, philanthropists have always been the second pillar for changing the world for the better. They have been using their self-generated and/or inherited financial abundance for creating or supporting institutions that benefit mankind (health, research etc.), or they have been committing themselves to other activities dedicated to the common good.

In the recent past, even private sector companies have become more and more aware that – being part of the global society – they should also assist and promote its development and improvement. The main goal of their activities, of course, remains the promotion of their very own economic interests, i.e. they aim at risk-adjusted profits in conformity with the market.

An increasing number of investors, however, have turned to a relatively young investment method, Impact Investing (IMPIN), which is not only about achieving a monetary ROI, but also about achieving value-centered objectives.

Looking at successful entrepreneurial activities from the viewpoint of acting responsibly in our global village, we can distinguish two approaches:

- For which purpose do enterprises use the financial resources they generate?

- How do enterprises generate revenues?

The first question examines measures of entrepreneurial action taken according to the Anglo-Saxon paradigm “Do good and talk about it”: Cultural or sports sponsoring, philanthropic activities such as granting scholarships, donations, establishment of foundations or direct implementation of projects that are socially relevant.

With regard to our problem, however, the second perspective takes priority. It won’t bring up feelings of “doing-good” if a foundation invests its capital in shares of oil majors, for example, and then, from its dividends, fights the ecological, health-related or economic impacts of oil disasters. To generate this feeling, the foundation would to have to invest its money in companies whose business models are compatible with the foundation’s actual purpose.

People, Planet and Profit

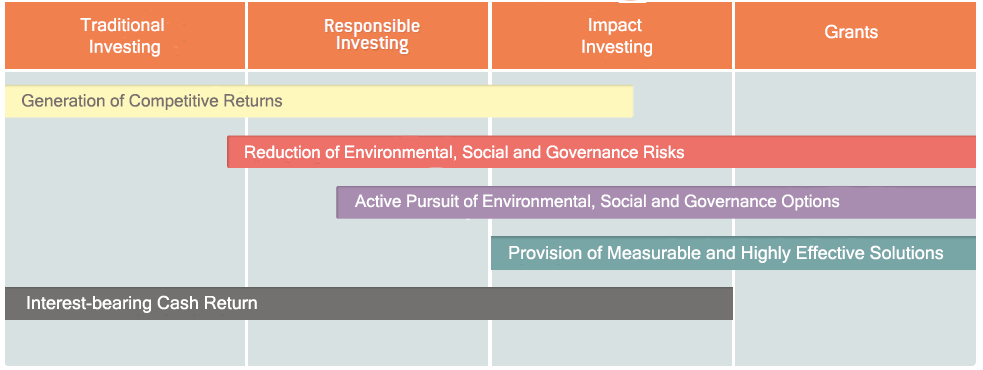

The desire of investing money sustainably, i.e. in a way that benefits “people, planet and profit“, leads investors, in a first step, to excluding target companies from those sectors that are not compatible with personal values and ideologies. In most cases, investors apply such “negative screening” for purchase decisions regarding shares or bonds.

In doing so, they exclude emitters with undesired activities from their scope of decision. This can apply to specific industries (arms, alcohol, tobacco, oil etc.), users of specific methods (animal testing, genetic engineering etc.) or companies that conflict with specific religious or ethical ideas (abortion, pork meat products, child labor etc.). It further excludes investments in countries with dictatorship, corruption, death penalty, use of nuclear energy or non-execution of disarmament or environment protection agreements.

Such rather subjective value-based decisions are, on the one hand, not always clearly sustainable and, on the other hand, may lead to obvious negative consequences in other economic and societal areas.

Already, many companies all around the world are acting upon the maxims of classical Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). As a rule, these companies publish reports on their ESG activities (Environment Social Governance Information) along with their financial reports. This allows investors to orient themselves towards Socially Responsible Investments (SRIs).

New Orientation Methods for Sustainability-Oriented Investors

The scope of action for sustainability-motivated investors is thus expanded by two more selection methods with regard to impact investing:

First, the availability of rating procedures for evaluating the ESG activities of companies enables positive screening within the CSR universe. Only those enterprises are selected for the portfolio that can offer the best ESG ratings, or those that are best in different industries with diversified performance (best-in-class approach), respectively.

The second method is referred to as ESG integration and, in its analysis of investment objectives, is no longer limited to evaluating financial reports but also includes ESG reporting into the decision-making process. This, of course, requires accessibility to the required information. ESG integration as a decision-making procedure is therefore, above all, used for listed companies.

Companies which – below the bottom line of their profit and loss statement – also offer societal and environmental commitment are referred to as “triple bottom line companies”. Assessing such companies by measuring the future cash flow against the risk-adjusted capital costs, ESG factors such as stakeholder interests, pricing, reputation, economic use of labor and resources, financing as well as rules and standards of corporate governance are evaluated in view of their impact on future cash flows and integrated into the evaluation of the enterprise as a whole.

Various studies show, by the way, that taking ESG factors into consideration does not negatively affect the financial performance of a company regarding additional costs or limitations to market exploitation.

Limitation in the Selection of ESG Compatible Investment Options

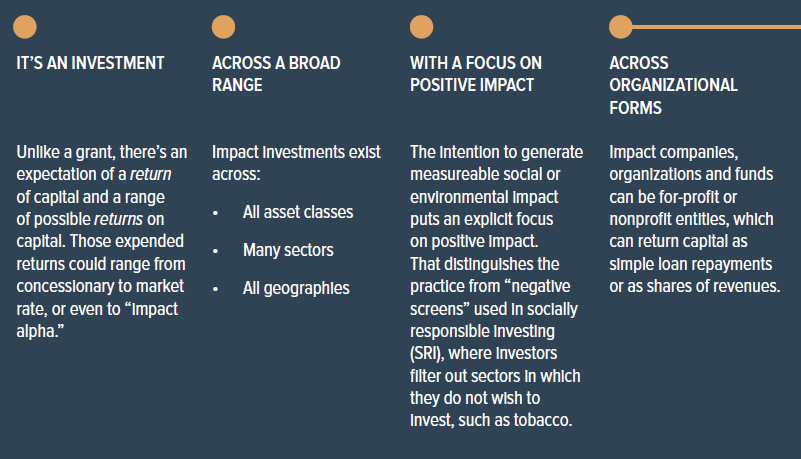

Since 2007, the term “Impact Investing” (coined by the Rockefeller Foundation) marks yet another limitation in the selection of ESG compatible investment options. Regarding this, the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN), a non-profit organization for promoting IMPIN, suggests the following definition: “Impact Investments are investments made into companies, organizations, and funds with the intention to generate measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return.“

IMPIN is distinguished from philanthropic activities insofar as the reflux of the invested money plus a profit is indeed expected. What they have in common is that some philanthropic funders, foundations with charitable goals, for example, do not consider their support as “lost” grants but instead, are eager for generating profits from their investments that are customary in the particular market (mission-related investments) – or they are only willing to make concessions regarding the targeted profit (program-related investments).

Philanthropic and IMPIN capital investors, hence, are looking for target companies that submit to ESG requirements, but at least return the investment. Regarding profit, some capital providers expect profits that are customary in that particular market (non-concessionary investors); others are willing to compromise – or even to renounce any profit altogether (concessionary investors).

The basic difference between IMPIN and the ESG selection procedures are the criteria of “intentionality” and “measurability”. Thus, the target group for IMPIN are not companies that, in addition to their core business, demonstrate a bit of ESG orientation, but rather companies for which the societal and environmental impact is the objective and purpose of their activities. Such an impact requires additionality, i.e. without the respective entrepreneurial initiative, just by pure market dynamics, the desired effect would not happen. And in order for the intended impact to take place, it must be measurable and such measurement must be actively pursued by the company.

There are, of course, a host of issues when pursuing an IMPIN: What are the companies that proactively pursue the desired societal impact, and how to find them? How to measure these “impacts” and what about the measurement’s reliability? Where and who are the institutions and intermediaries that support selection, monitoring and measuring of the investments, and how reliable are their instruments and tools?

Above all in the USA, but also in Europe, an infrastructure of organizations for the support of investors has emerged. In the second part – soon to follow – this infrastructure will be outlined.

Sources:

- Berrisford, C.: To integrate or to exclude. Approaches to sustainable investing. UBS (2015)

- Brest, P., Born, K.: Unpacking the Impact in Impact Investment. Stanford Social Innovation Report (2013)

- Drexler, M., Noble, A.: Charting the Course: How Mainstream Investors can Design Visionary and Pragmatic Impact Investing Strategies. World Economic Forum (2014)

- Greene, S.: A Short Guide to Impact Investing. The Case Foundation (2015)

- Petrick, S., Birnbaum, J.: Social Impact Investing in Deutschland. Marktbericht 2016. Kann das Momentum zum Aufbruch genutzt werden? Bertelsmann-Stiftung (2016)