The following article contains the transcript of this year’s MBS Semester Opening Keynote Speech, held by Dr. Alfred Gossner, the new President of Munich Business School.

Dear Mr. Baldi, dear MBS students, ladies and gentlemen,

I would like to welcome you to this year’s Semester Opening. Many of today’s attendees – especially the professors, lecturers and staff employees of MBS, but also the “older semesters” – have already experienced similar events in the previous years. For others, such as the freshman students and myself, it’s a premiere. For all of us, however, it is the beginning of a new year of shared working and learning.

A few days ago, when I was thinking about what I should say to you on this occasion, it struck me that this is not an easy task. Allow me, therefore, to make a few preliminary remarks, also in the sense of effective expectation management, so as not to set the bar too high.

- I was not given a topic, which I can decently process according to the usual criteria.

- This is my first such event, thus, I cannot revert to historical experiences. Prof. Dr. Baldi has simply ignored my gentle suggestion that one of the speech transcripts of my predecessor might have been of some help to me here. I believe one may assume that he did this on intention, and perhaps it even was a good thing.

- I do not really know you nor MBS, and therefore I cannot estimate to what extent general reflections on the role of science and the duties and responsibilities of universities in educating young people for future careers as managers or entrepreneurs apply to MBS. In this respect, you cannot – as defined by my expectation management – expect a programmatic speech, because this would require a review of the current state.

- My already tight time budget, as long as I am still a Member of the Executive Board of Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft, has been further reduced during the last weeks by a serious sports accident of my wife. I may quote Goethe here, who once began a letter to his sister with the words: “I have little time, so I am writing you a long letter.”

First and foremost, I will address myself to our students with the following considerations. You take the center stage; in the end, it is you for whom MBS exists.

What Can Students Expect From the Sciences?

You, the students, have decided to prepare for or further your career in primarily commercial fields of activity by means of an academic education. This is – especially in the context of a private university, which has to charge tuition fees – an “investment decision” from an economic point of view: You invest in your human capital, and as a return, you probably expect a more attractive career path in superior positions, which should enable you to achieve both higher financial returns and a higher level of personal satisfaction (i.e. self-assessment, social status). Of course, there are also other reasons that impact the decision to study.

In this context, important questions to me seem to be the following ones:

What can you expect from your scientific activities (and thus from the sciences themselves), and what should you consider in view of scarce resources (and the scarcest resource is always time) when you are dealing with the sciences – on your part, but also on the part of the university – so that you benefit as much as possible for your future life – both professionally and privately?

These are no simple questions, and they cannot be answered conclusively in such a semester opening speech. But because I have no interest in acting only as a friendly “figurehead” here, I will still try to do it, although many aspects will remain sketchy.

In good academic tradition, one would first have to define “science”. This task alone would take ages. I therefore use a very simple definition: Science is the activity in which “the state of things” is systematically described and investigated using objective and reproducible methods. “State of things” includes physical objects, biological organisms, social systems, but also concepts, issues, values, situations etc. “Objective” (or justifiable), “reproducible” (i. e. transparent) and “systematic” are the keywords. This definition primarily implies an activity and a mindset, not an institution, subject delimitation or cultivation of tradition.

“Nothing Is as Practical as a Good Theory”

I would like to briefly address two key aspects of engaging in science:

- Science almost always has to do with two intentions: The first one – also in historical development – is the recognition of facts, of what ultimately appears to us as reality. On the basis of recognized correlations, principles etc., it is followed by the shaping, i. e. the conscious influencing and changing of reality or the conscious creation of objects. Let me give you a few examples: Based on scientific findings in physics and geometry, engineers have developed the rules of statics, which allow us to build fairly safe bridges or high-rises. Based on physical findings on the structure of matter on the atomic level – electrons etc. – modern micro- and nanoelectronics was developed, enabling us to process data and signals at enormous volumes and speeds, thus creating the basis for digitization.

- Do not be tempted to believe in the alleged contradiction of theory and practice, which is invoked above all by those who do not understand the theory, its intentions, but also its limitations. David Hilbert (the great mathematician) is right with his statement “Nothing is as practical as a good theory”. The emphasis is on good, i. e. an accurate and thus also relevant theory.

The Three Levels of Scientific Encounters

You encounter science – or rather, you should encounter it – during your education, but also in your subsequent professional life, mainly on three fields or levels:

-

The Level of Your Chosen Scientific Discipline

In your case, these are economic and business sciences with special consideration of the subdisciplines that deal with management (usually of companies). First of all, this involves the recognition of economic organizational forms, their structures and processes, especially along the value-added chains, the interaction of essential functional areas from procurement to production to marketing, the mapping and measurement of activities in information and control systems, the interaction with the economically relevant environment of organizations, which has a significant influence on the processes and results of an organization. Explanations of terms, typologies and the description of cause-effect correlations are in the foreground.

After recognition, however, it is primarily a question of shaping organizations in the sense of goal-oriented management, whereby the goals usually appear to be predetermined to the management (by the owner, but also by the constraints of competition). Structures, processes, functional areas and systems are to be optimized in order to enable optimal goal achievement.

You should get to know your particular scientific discipline in detail, i. e. the essential methodical approaches, their findings and limitations, the available tools (e. g. from statistics) to analyze data, for instance, etc. It is expected – in practice – that you are able to apply the analytical framework and the tools of your scientific discipline to different operational situations in order to govern them and, above all, to further improve them in the sense of achieving goals. This ability to transfer must be promoted above all else, it does not succeed on the basis of passively learning book contents. Case studies are a good way to train this competence. Instead of merely reproducing theoretical concepts or methods without a concrete context, case studies allow you to learn how to apply and combine those abstract concepts and tools, the selection and use of which is determined by the practical problem of the case.

What role will science play in your future work in companies? This will of course depend on the type of activity and therefore cannot be answered in general. From my personal experience of almost 40 years on the job, including more than 32 years as a manager (27 of which as Chairman or Member of Executive Boards), I would like to say that for management tasks, i. e. making decisions on activities and programs in complex situations with often very limited information, managerial theories and instruments in direct use may account for 20 to 30 % of the solution, while the rest consists of situation-specific analysis and experience. That sounds sobering. However, it does not mean that such academic education is not worthwhile. Although you will rarely be able to consult a textbook in a concrete situation in a company and find the solution there with pinpoint accuracy, the ability to approach a situation critically and impartially, to use analytical instruments where they promise additional findings, and to think in complex systems in particular, i. e. to incorporate the essential cause-effect correlations and feedback into your considerations, is a very important one. In this sense, studying a scientific discipline is in some ways like good training, which enables an athlete to achieve a special physical performance in a competition.

-

The Level of Natural and Engineering Sciences

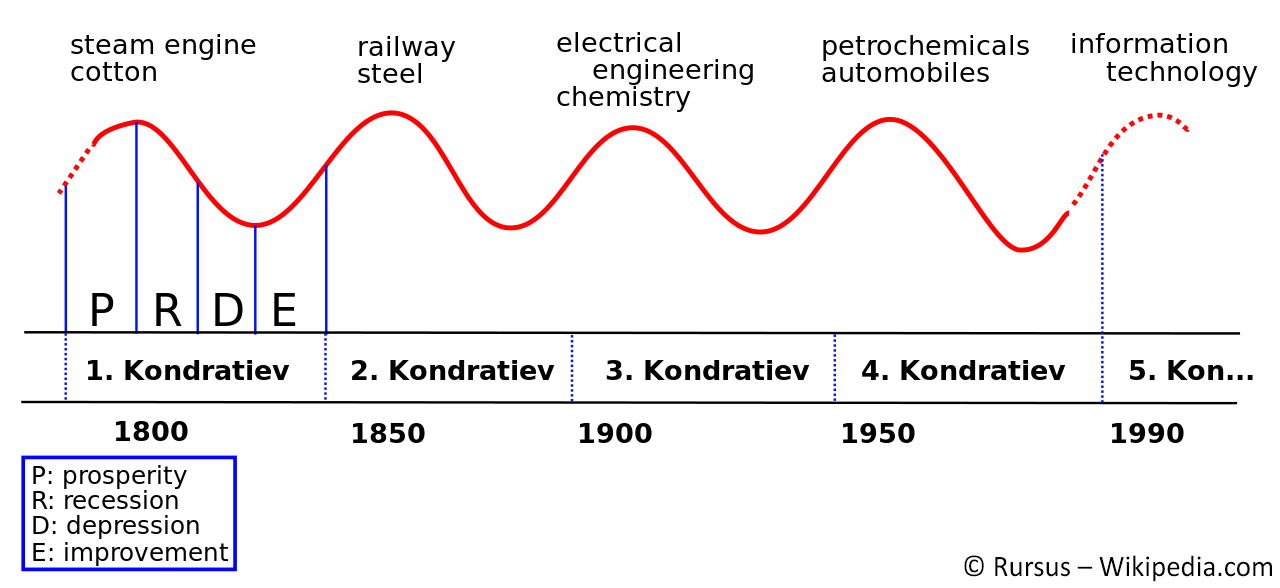

You will also encounter science in the form of the technological and natural sciences. Understanding and, above all, shaping economic organizations inevitably involves recognizing and understanding an organization’s economically and socially relevant environment. The first question is: Which environmental factors have an impact on the organization today – in a stimulating or constraining way? The second, and even more complex, question is: How will the economic and social (political) environment change, what are the development processes it is subject to, and how will these changes affect the organization? It is trivial to state that our modern world is increasingly developing under the influence of scientific and technological breakthroughs, and that such innovation surges come along with considerable economic and social disruptions. A popular description of these processes are the Kondratjeff cycles, named after their discoverer, the Russian economist Nikolai Kondratjeff, which perceive the development from about 1780 to 1990 as shaped by five major technological waves or phases:

- Steam engine and industrialization (mechanics, iron);

- Railway, telegraphy, photography;

- Electrification, automotive, chemistry;

- electronics, nuclear power, plastics, aerospace;

- IT, Internet, consumer electronics.

The sixth Kondratjeff cycle is often puzzled about. For me personally, there is no doubt about that digitization is or will be a central element of this phase, with the importance of which as a cross section technology and trend being already evident.

Digitization is currently in the process of redefining entire industries and replacing existing business models with new ones:

- On its platform, AirBnB organizes more accommodation in the world than any other player in this field – without owning a single hotel.

- Uber is revolutionizing the taxi industry without having an own vehicle fleet – at least where there are no efforts to prevent this form of sharing economy through regulation.

- The technological breakthroughs facilitated by digitization (artificial intelligence, machine learning, analytical analysis of big data) and sensor technology, some of which are already available or are expected to be achieved in the near future, should lead to self-organizing production and logistics processes across value-added chains and to the loss of millions of jobs in manufacturing as a result of this “industry 4.0”. New jobs for developing and operating such systems will be created.

- The components of digitization mentioned above will also be used – in combination with new communication networks such as 5G – to enable autonomous driving, i. e. to independently move vehicles that communicate with each other in road traffic. This will optimize traffic flows, significantly reduce the number of accidents and make professional drivers unemployed.

- Finally, digitization will change the way we teach and learn, and thus affect our own business here.

Similarly, other technologies with disruptive potential (quantum computing, robotics, renewable energies etc.) could be commented on.

These technological upheavals will lead to dramatic changes in companies and economic structures, which will no longer be overcome by gradual readjustment of proven processes and structures.

If you are to be responsible for a company in the future, you should not only understand the forces that have shaped the current environment, but above all the technological developments that can and should be expected. In short, you should understand the main findings of the natural and engineering sciences and their economic and social implications. In contrast to your scientific discipline, this is not about turning you into natural scientists or engineers, especially since today nobody can master the entire range of these subjects in the scientific depth of their individual disciplines.

However, in a business school, we will together with the students have to think more intensively about how we can develop this understanding of economic and social implications of technological change and disruptions in a targeted way – and thus strengthen your practical application competencies. In addition to providing basic knowledge, I also perceive technologically based case studies as an interesting way of doing this.

I have to admit openly that as a young doctor of economics I would probably not have made such statements. I was not a neoclassical supporter of equilibrium theories, but rather dealt with macroeconomic imbalances and the induced dynamics of employment, wage levels etc. The significance of technological dynamics and disruption for the development of economies and companies, which Joseph Schumpeter already referred to, did not become apparent to me until my occupation at Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft.

-

The Level of Values and Culture

A third level on which you will – or should – encounter science relates to the topic of “values and culture”.

Values as important part of a “culture” shape people’s behavior, their motivation, team spirit and sense of responsibility. A shared and actively lived value base of a company’s employees will often have a greater impact on the company’s achievements than individual business-optimization measures or strategies. As the Americans say, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast – and structure for lunch.”

Values are reflected in the cultural sciences and the humanities, and especially in philosophy. The origin of value systems in human communities is complex and scarcely susceptible on short notice. Today, we often still live on values that have arisen in earlier times and will not necessarily be widespread in the future. In his work “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism”, Max Weber impressively analyzed how typical attitudes that are important for a market economy originated – such as the proverbial “Swabian diligence” in the wake of Calvinism and its asceticism, i. e. of a specific Protestant form of religion.

In a company, however, it is not only about understanding which values motivate and influence employees, but also about actively shaping and justifying values. This is not only about the personal values that motivate individual people, but also about the values of the company/organization, which ultimately form the basis of its goals. In the literature, these goals and values have traditionally been taken as given from the economic point of view, by the owners, supervisory committees or the constraints of competition. Milton Friedman summed up this point of view in a nutshell: “The business of business is business”. A discussion of values is therefore neither necessary nor possible.

I do not share this point of view, and I believe that it is important for management to approach value-related issues in a credible manner. I see three main reasons for this:

- Values are not objectively and unambiguously deducible like mathematical theorems. This has been clearly demonstrated by the history of philosophy, which is full of attempts to justify or refute value hierarchies. If one makes additional assumptions, such as the existence of God in Christian theology, the derivation of a canon of values is relatively simple. The plurality of possible value systems has often led to an attitude of value relativism – anything goes – or even to the rejection of “value” as a philosophical category. In his “Tractatus logico-philosophicus”, Ludwig Wittgenstein once said: “There is no value – and if there were, it would be of no value.” Rational justifications of values are absolutely possible though, as J. Rawls has shown in his “Theory of Justice”.

At the level of social organization, values are no longer derived from philosophical premises, but are often set by qualified majority decisions, e. g. by a constituent assembly or a resolution of states such as in the case of the UN Declaration of Human Rights. In this way, they derive their validity and legitimacy from qualified acts of voting.

- Despite the fundamental plurality of value systems, people in all cultures have a need for values that serve as orientation for individual and community acting. Basic values such as the protection of life and health against arbitrary attacks are similarly pronounced in most societies. In short, we human beings need common values. The reflection and discussion of common values strengthen team cohesion.

- The values and objectives of stakeholders (external) and employees (internal) do not automatically fit together perfectly. One of the central tasks of top management in particular is to mediate and make these value systems compatible.

In sum, “values” are one of the great challenges in management. It is obvious that we cannot influence them at will, for example to promote economic objectives. “A new culture by tomorrow” is not possible. It is also obvious that we should not just leave them to their own devices. Values convey meaning and motivation to people, and a vacuum can quickly be filled by obscure advisors and ideologies. In management, we should be able to engage in a dialogue about values not as an indoctrination, but as a tool for self-reflection.

This dialogue on values and the ways in which they can be justified should therefore form part of a management-oriented education. The MBS values “think innovatively, act responsibly and live open-mindedly” are a very good starting point here.

Please allow me another personal comment here: As a young manager at Allianz Group, I have not been particularly aware of the importance of values and the reasons for them. In retrospect, it was because I had then worked with a relatively homogeneous team of young people who shared similar values.

This importance, though, became immediately clear to me when I moved to Johannesburg as the CEO of Allianz South Africa, where apartheid was about to end and the transition to a new political system took place. Here, there was a discussion in the media, but also in companies, on very different value systems in the process of organizing economy and society almost daily.

Learning to Think

Dear students, I hope I have been able to convey to you that in my view science is important for your education, in a broad but differentiated understanding. This is not about scholastics, i. e. the learning of an accepted academic knowledge canon, which you can then reproduce as accurately as possible. It is about “learning to think” and, more precisely, “practical thinking”, which is aimed at solving real problems. This is a dialectical process: One learns a systematic or methods of e. g. marketing or business valuation and then uses them to solve practical problems. Practical application in a case can certainly lead to improving systematics and methods.

I consider the “Science of Management” primarily as a science of action, which helps us to optimally prepare and implement complex decision-making situations using the available resources.

Ultimately, it is a matter of educating and developing personalities who are capable of making decisions and acting, and who can and want to assume responsibility on the basis of well-founded and lived values as well as professional expertise. This holistic approach seems to me to be an essential goal of MBS, and at the same time an important motive for my commitment.

This goal of holistic personality development is not only a reflex of humanistic traditions in Europe and thus a luxury we want to afford. It rather is a sheer necessity in the modern world, whose complexity and upheavals are clearly increasing. We will not succeed without a value-driven, professionally well-founded management that takes into account global developments.

I would like to explicitly ask you to understand your studies in this sense, and you should demand that.

“There’s Always Room Upfront”

This brings me – very briefly – to the “other side” of the house, the lecturers and employees of MBS, who are to offer you high-quality education. The brevity of this part does not mean that I disdain your work. But in addition to the tight time budget, it can also be justified by the fact that my considerations regarding the organization of studies automatically give rise to tasks and responsibilities for you – and me – as a service provider. We must develop and offer the aforementioned high-quality content, we must facilitate and demand critical discussion, and we must also justify and live values in a credible manner.

For this, we need the enthusiasm of the lecturers and no “uninspired teaching personnel”. Personality development and education ultimately take place in exchanges between people, and not through the use of technical systems. We will critically examine what new possibilities e.g. the digitization offers for MBS, in particular whether it will give us additional scope for personal encounters between lecturers and students.

If we succeed in meeting the requirements outlined here at MBS, this will also have a positive effect on our position in the university competition. You might then quote Michael Schumacher, who once said as for Formula 1:”There’s always room upfront.”

Ladies and gentlemen, I wish all of us a successful academic year, and a happy Semester Opening ceremony with new encounters and good conversations today.